Bangalore, India’s bustling IT capital, has seen remarkable population expansion in recent decades. According to the most recent UN World Urbanisation Prospects estimates, Bangalore’s population will be 14,008,262 in 2024, up significantly from 745,999 in 1950. This expansion equates to an increase of 400,462 people in the last year alone, representing a 2.94% yearly change. These estimates include both the core urban population and adjacent suburban areas, representing Bangalore’s large metropolitan agglomeration (a metropolitan city having a population of over ten million).

The Decline of Green Spaces and its Implications

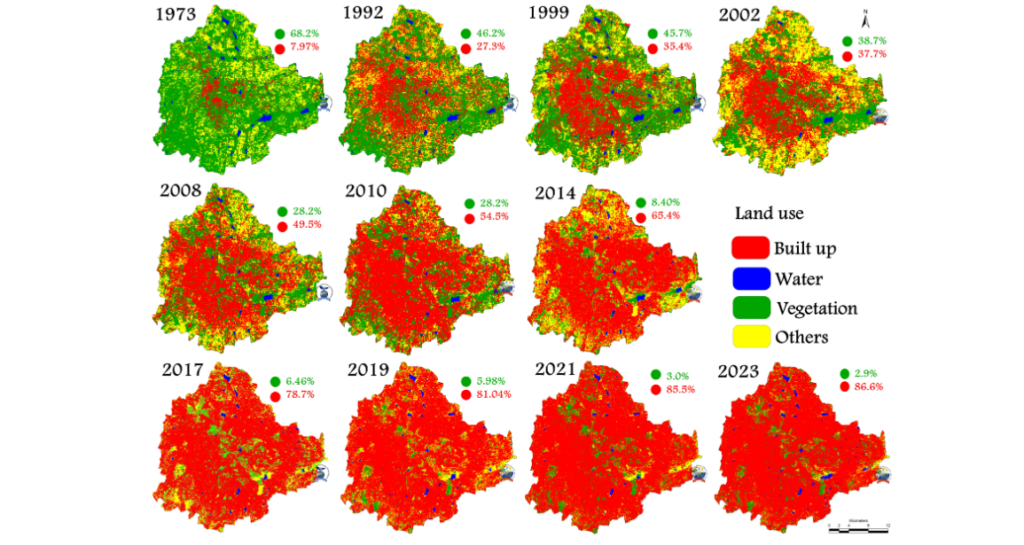

In the 1970s, Bangalore thrived with 68% green cover. It is now less than 4% due to rapid urbanisation and questionable planning. This stunning fall highlights the critical need to balance environmental protection and development. The IT boom of the 1990s brought unprecedented economic growth but at a heavy cost, as evidenced by the alarming reduction in Bangalore’s green spaces and wetlands, which have further resulted in many sustainability and liveability challenges, including poor air quality, water scarcity, decreased groundwater retention, biodiversity loss, a rising urban heat island effect, reduced walkability, and increased public health issues.

A 2017 study found that Bangalore has approximately 2.2 sqm of open space per person – a far cry from the recommended 10-12 sqm as per guidelines set by the Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD). Surprisingly, a study conducted by the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) revealed that the garden city falls embarrassingly short of meeting even the most basic green coverage standards, with people outnumbering trees by seven to one. Ideally, the city needs eight trees per person just to cover CO2 emissions from breathing!

Bengaluru’s Green Canopy: A Critical Lifeline for Urban Biodiversity

Bengaluru was India’s fifth most populated city in the 2011 census, following only Chennai with an estimated population of 8,443,675. Furthermore, the Karnataka Government’s Directorate of Economics and Statistics said that Bengaluru’s population had topped 14 million, representing a 48% increase over a decade. This extraordinary population expansion highlights the critical need to investigate the dynamic link between urbanisation and biodiversity conservation in Bengaluru. Despite its rapid growth, the city retains a rich natural diversity, with numerous species of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, insects, arachnids, and plants living within its urban habitat.

This ecological oasis remains in constant jeopardy due to increased urbanisation and unrestrained real estate development. According to studies, built-up areas have increased dramatically from slightly more than 2% in 1973 to nearly 49% in 2016, dramatically reducing the city’s abundant wetlands, agricultural land, and natural green cover. Despite these problems, the remnants of ancient trees, parks, and sacred groves continue to support a diverse range of species, highlighting their importance in preserving ecological equilibrium. For example, Bengaluru’s dense network of old-growth trees, which were planted during the colonial era, provides critical habitat for a variety of wildlife while also aiding in carbon sequestration and air quality improvement.

Another important aspect to emphasise is the significant cooling impact offered by green cover, which has been shown to reduce air temperatures by up to 5.6 degrees Celsius and road surface temperatures by around 27.5 degrees Celsius. This cooling effect would certainly make city life more comfortable, while also serving to offset the urban heat island effect, reducing the overall impact of rising temperatures in Bangalore.

Environmental Concerns and Citizens’ Perspectives

Findings from the Bengaluru Environment Report Card highlight citizens’ growing concerns about environmental degradation. The analysis identifies a gap between contentment with civic services such as water delivery and garbage management and discontent with fundamental environmental issues such as tree cover, parks, lakes, and biodiversity. The widespread land use change, loss of green cover, and overexploitation of groundwater demonstrate fierce competition for land and water resources, posing a danger to Bangalore’s natural endowment.

Why do trees matter?

Trees are the essentials of urban landscapes, providing a wide range of critical services that benefit people and the environment significantly. Trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, which helps to reduce climate change by storing carbon and releasing oxygen. This not only improves air quality but also helps to regulate global temperatures. Furthermore, trees serve as natural air purifiers, filtering out pollutants like sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, lowering respiratory ailments and boosting overall public health.

In addition to climate regulation and air purification, trees play an important role in urban stormwater management. Their massive root systems assist in maintaining the soil, prevent erosion, and absorb excess rainwater, lowering the risk of flooding and protecting vital infrastructure. Furthermore, trees provide important habitat and food sources for a wide variety of wildlife, increasing urban biodiversity and building ecological resilience. Beyond their environmental benefits, trees enhance the visual appeal of urban places by offering shade, quiet, and a sense of connection to nature for both inhabitants and tourists.

Trees are necessary components of healthy urban environments, and investing in their maintenance and expansion is critical to constructing healthier, more resilient cities for future generations.

Singapore’s incredible green journey

Bangalore can take inspiration from Singapore’s incredible journey to becoming a Garden City and, later, a Green City. In 1967, shortly after Singapore got independence, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew envisioned a future in which greenery would be smoothly incorporated into the urban landscape, improving the lives of its residents. This vision prompted major tree planting projects and the establishment of new parks, transforming Singapore’s roadways into verdant green corridors. Today, wandering down iconic thoroughfares like Orchard Road reveals the completion of this vision, demonstrating Singapore’s transformation into the Garden City it was meant to be.

Aside from being a Garden City, Singapore has worked to embrace the characteristics of a green city, as seen by its eco-friendliness, low carbon footprint, and abundance of green spaces. Singapore’s green areas have increased by 50% since 1986, despite a startling 70% population rise. This development will include classic parks and woods, innovative green construction efforts and vertical gardening projects. Singapore’s dedication to greenery is reflected by its National Tree Planting Day, which saw the number of trees increase from 158,000 in 1974 to 1.4 million in 2014. Furthermore, incentive programs such as the Skyrise Greenery Incentive Scheme and the Green Mark Scheme for Buildings demonstrate Singapore’s proactive attitude to sustainable urban development.

Singapore’s journey to sustainability provides useful insights for cities facing complicated challenges. Despite rising urbanization, the city-state has adopted innovative governance tactics to address wicked problems—complex situations that resist simple solutions. Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s objective for 1967 was to incorporate greenery into Singapore’s urban fabric, creating the groundwork for a Garden City. However, Singapore soon faced several complex difficulties, including housing constraint and environmental damage.

To address these difficulties, Singapore implemented a “Whole-of-Government” approach, emphasizing collaboration across sectors. This method promotes the sharing of knowledge and resources across a variety of stakeholders, including government organizations, enterprises, and individuals. Singapore promotes innovation and resilience in the face of urban complexity through inclusive policymaking and proactive public participation.

Also, Bangalore can take insights from Singapore’s Green Towns Programme, a 10-year goal to make HDB towns more sustainable and liveable. The program aims to reduce energy usage, recycle rainwater, reduce trash, promote green commutes, and chill HDB towns. By implementing comparable ideas suited to its context, Bangalore can further improve its efforts towards sustainability and create a more environmentally friendly urban environment for its citizens.

As Bangalore continues to grow, creating and conserving green spaces must become the top priority. Efforts to promote urban reforestation and afforestation must be supported by robust policies and community involvement to ensure the city’s long-term viability and resilience. Bangalore may strive for a greener, healthier, and more liveable urban landscape by taking cues from past mistakes, environmental research, and proven case studies.

Sources:

Bangalore Population 2024

Green Spaces in Bengaluru: Quantification thought Geospatial Techniques

Biodiversity in Bengaluru A manual for journalists reporting on urban biodiversity

A case study of Singapore: A garden city that is not so green

Challenges and Reforms in Urban Governance